Dear Oman,

In June, I was forcefully made aware of the illusion of peace. you showed me what it truly looked like.

That month, an all out war broke out in my home country, Iran. My 18th summer— the only summer I had before my first year in university— took on the bleakest of colors and lost all its vibrance.

I had been there for 2 weeks, excited, making plans for the rest of summer. But soon enough, I was looking for guides on preventing window glass from shattering. Thoughts of enjoyment and adventure turned into ones of survival and safety.

On more than one occasion I wondered to myself if I would live to see tomorrow or not.

And when a missile struck 2 kilometers away from home, my family decided I was not to stay in Iran any longer. With the airspace shut down, they arranged for me to travel to Bandar Abbas alone to search for any vessel that could take me out.

And that’s when I heard about your ships, Omani ships, carrying civilians back to Oman. After the 8 hour bus ride to the port, I visited your makeshift embassy at Ghods hotel. I pleaded with your delegation. I wasn’t an Omani resident, but I promised I would go straight to Qatar. I begged. Hours of back and forth passed, until I was finally offered a spot on your ship.

It was all over. I had found a way out. I was safe.

Until again, life reminded us all of the illusion of peace.

The port your boat was docked in was struck. I remember the entire boat shaking. I pulled the window open and saw the scene outside.

The water rippled and reflected the bright hue of chaos. I took a picture before being told to turn my phone to flight mode.

Screams, questions, and cries burst throughout the ship.

You instructed your ship to go into blackout mode. For a moment, everyone went silent. The lights went out. The only light entering the ship was that of the blazing scene outside— peering through the blinds. The ship remained docked.

And yet again, life reminded us all of the illusion of peace.

Another blast, this one closer. Off to the right. This time the windows rattled. People fled from the windows.

Your ship started moving this time. We floated through the water, away from the port. The window blinds glowed an eerie red, illuminated by the destruction outside.

Your officers asked me how I felt. 4 weeks later, I still don’t know what I was feeling, really; at first I thought I was numb to it. That if it was in the stars for me to perish, I would’ve done so that night. One moment alive, the next under water. But I realize I was not numb to it. In moments like these, your body takes control of your conscience and you enter a fugue state. Autopilot.

Only afterward do you grasp the damage done to your conscience. For that reason, I am grateful I found myself in your country in the aftermath.

The rest of the ride there was oddly serene. Some slept; others stared at the horizon, confronting how fragile and helpless we truly are. We were adrift in a boat, in the middle of the Strait of Hormuz. The Strait of Hormuz. The same place I had constantly read about on the news. “Volatile body of water”. “Threatens closure and disruption”.

When we finally got to Khasab, your captain informed us that because of the situation at the port, none of our luggage could make it. You had kept it safe back in Iran, away from the port.

For the residents of Oman, this was fine— they had homes and visas to stay. I was not a resident. The fact I was even on your boat was because of the sympathy of your officers. And now I was in your country, with my passport, phone, and practically nothing else. I was stunned and alone, too confused to fathom what was happening and what I would even begin to do.

And then, you reminded me I was in safe hands.

At customs, your officers assured me it would all be fine. They gave me numbers to communicate with and people to reach out to. You issued a temporary visa for me. Most of all, they gave me what I desperately needed—assurance.

I believe this protected my conscience, or at the very least mitigated the impact of the sights I had just seen.

The sun had started rising at the port. I remember recalling how beautiful the landscape was. On my right were rugged brown cliffs and shrubbery, and on my left was the wide ocean, a pale blue.

You directed us towards buses, and we started heading away from the airport. Conversation soon filled the aisles as us passengers— bound by shared terror and relief— began to process what had happened. Everyone had a different perspective, be were all grateful; grateful that we were alive, and we had you to thank for that.

We made it to Atana Khasab— the hotel you had allocated for us. We were rushed to the buffet while the receptionists prepared rooms for us.

It was grim, really. But I remember finding it so funny at the time. Perhaps it’s in poor taste to find humor in war and destruction, but I was genuinely amused by the absurdity of it: just hours ago, I had been trapped in a warring Iran, running on nothing but willpower, begging for a place on your boat. And now, here I was in peaceful Oman, eating braised salmon at a luxury hotel.

What I suppose I mean is— I felt so untethered from my life. I felt like an observer, watching forces shove and nudge my body across the world. I had quite literally lost control of the steering wheel. I didn’t know what the next hour would bring, let alone tomorrow. And the stark difference between that feeling— the lack of control, the helplessness— and the life I once knew struck me as, in some macabre way, funny.

Artist Bo Burnham once called it “that funny feeling”— total disassociation, fully out your mind. googling derealization, hating what you find.

I didn’t really know what I was, only that I was fully disassociated. A violent quake had come and split my life into pre-war and post-war Faisal— and I wasn’t in control of what was happening to post-war Faisal.

But I was, yet again, assured by your delegation that everything would be alright. I suppose I had lost control of the steering wheel, but I’m grateful you had reached out and taken hold.

In that way, you reminded me yet again, that I was in safe hands.

In my room, I rinsed the chaos from my skin, hand-washed my only set of clothes, and fell onto the bed, weightless. Through the window, I watched the sea breathe, the waves catching the first hints of dawn. Birds began to sing and pierced the stillness of my mind. The sky, bruised with the memory of night, began to brighten.

And somewhere between the ocean’s breath and the chorus of mo(u)rning, I drifted to sleep.

I woke up to the ring of the hotel telephone.

“Breakfast is served! Make sure to come grab a bite before leaving for Muscat.”

I slipped into my barely dry clothes, gathered the few belongings I had, headed downstairs. Despite all that had happened, I had an insatiable appetite. I piled two plates up with food and sat in the smoker’s lounge. I don’t smoke; I just wanted to be around other people. I didn’t want to be alone with my thoughts.

I started feeling alive again. Breakfast in front of the turquoise sea— the horizon splitting the view into two different shades of blue— one noticeably darker, more mysterious than the other. pre-war and post-war me, I thought. The panorama of blue was ocassionally joined by the earthy wafts of steam rising from my cup of coffee. Now and then, a thread of cigarette smoke pierced through the lounge, sooty and deep, keeping me grounded to reality. The sounds of people conversing in Farsi, talking about their relatives or homes. And maybe, just maybe,

I saw someone’s eyes crease as they let out a hearty laugh.

And for that instant, I let myself believe in safety again,

because of you.

Like all good things, my moment of peace eventually came to an end. But it filled me with warmth and security— feelings I craved far more intensely than my gnawing hunger.

We boarded your buses yet again, this time bound for the airport. As we pulled into the departures entrance, I quickly realized that this was no regular terminal. You were escorting us aboard your own Royal Airforce.

Again, that funny feeling bubbled up in me. How surreal this journey had been, and how much stranger it was about to become, being carried to safety by a royal aircraft. Who would’ve even thought? Just 2 weeks ago, I was enjoying Iran, surrounded by family. Now, I was somehow in Oman, alone, slowly losing control. But perhaps losing control of the trajectory of my life wasn’t so bad, as long as you were steering the course.

We were guided across the tarmac towards the silhouette of your Lockheed C-130 Hercules. I remember thinking of how well the sand-green camouflauge worked. The military plane almost melted into the mountains behind it, only your flag interrupting the illusion. That funny feeling possessed my body. I sank into the seat, weightless, resigned to forces far greater than myself.

As the engine started and rumbled, our bodies were pressed into the seat, subjected to force of weightlessness. Oh, the mysterious mechanics through which life operates. How did I end up on the Omani Royal Air Force’s warplane?

Answering myself, I whispered part of an old quatrain I had memorized.

با چرخ مکن حواله کاندر ره عقل

چرخ از تو هزار بار بیچارهتر است

Blame not the heavens through the reasoning mind,

For the heavens are a thousand times more wretched than you.

Perhaps that illusion of peace— the one life had shattered without hesitation— came from thinking the heavens had our best interests in mind. That they were gentler than our world. Our world, enraptured by war, riddled with destruction, steeped in inequality. But they were not. Their decrees were, if anything, a thousand times more chaotic and indifferent than we could bear to imagine.

I repeated this couplet to myself, until I felt the stillness of sleep take over my body once more. Through clenched teeth, I whispered it again and again, a chorus of mourning against the engine’s chorus of war.

And I drifted off to this duet of chaos and resignation.

I instantly knew that we had landed when the ramp of plane opened and the humid, sticky air filled the cargo hold. I jolted awake and looked around, half-expecting it all to be a dream.

We were led to the arrivals terminal. For many, the journey was over— they were residents. But what home did I have in a city I had never set foot in before?

I spoke with your officers about what would come next. They told me that you would be in touch and inform us as soon as our luggage arrived. I got the feeling that I was on my own now, finally responsible for what would come next.

I installed your country’s analog to Uber, Yango, and ordered a cab to the cheapest hotel I could find.

I assumed the pleasantries were over. That your plan for me had run its course. I’d been handed back the steering wheel, sent off in a direction unknown.

But then Ahmad— the Omani Yango driver picking me up from the airport— noticed.

Ahmad realized something was off immediately and asked what was wrong. I wasn’t exactly in the mood to describe everything; I just said I was going through a rough spot. He asked how I’d learned Arabic despite not being Arab, and I briefly explained my upbringing. He listened with so much sincerity and patience, then said:

“I live here and know people. You are our guest. If you ever need anything, we are here to serve you.”

And perhaps he was just offering. Being polite. But it stuck with me.

Ahmad was the first person I met outside of the chaos of war, and he reminded me life could still be normal, peaceful even. But beyond that, he also set the tone for my unplanned stay in your country.

I didn’t know it yet, but I would feel that same generosity again in Oman. And again. And again. In fact, every single local I met was unbelievably welcoming. It didn’t feel like mere formality— these people, your people were genuinely concerned, eager to help in any way they could.

And it wasn’t even out of pity— I didn’t tell any of them how I ended up in Oman. These people rushed to help someone they didn’t even know. All they knew was I was visiting, and that was enough for them to immediately offer whatever they could.

I wasn’t expecting pity— let alone kindness. I wasn’t expecting anything at all, really. After everything that had unfolded, I had almost forgotten what kindness really felt like. What surprised me was that the kindness I encountered wasn’t out of pity or obligation— it was genuine kindness, a sincere eagerness to help someone out, just because you can. A choice to be good. Your people reminded me of that.

I could write a whole book about the sheer kindness I experienced during my stay in Oman, but even that would fail to describe what it felt like being surrounded by your people.

If I were to try to describe it, however, the word I’d use is peace. I felt at peace. Despite everything, despite the displacement, despite the bombing, despite it all, I felt at peace in your land.

Ahmad, like almost every other cab driver, did not accept payment for the ride. They insisted. Gave me their phone numbers.

At the hotel, the manager upgraded my room for free. The receptionist gave me his charger until I could buy one.

Other cab drivers offered coffee, tea, dinner. Very few of them accepted payment.

Sales associates at Amouage gave me extra samples, never got bored of seeing me. When I paid with cash and they didn’t have change, they ran to an exchange spot to make change for me.

When I was alone at the beach, people came up and talked, bought me drinks.

One elderly gentleman even insisted I pray with him at your Sultan Qaboos Mosque.

These interactions made me feel at peace, but I was also dumbfounded. The contrast between what my life was a few days ago and what it had started to become, what had formed around me, was abrupt. War had shattered my perception of peace. But you reframed it. Rebuilt it.

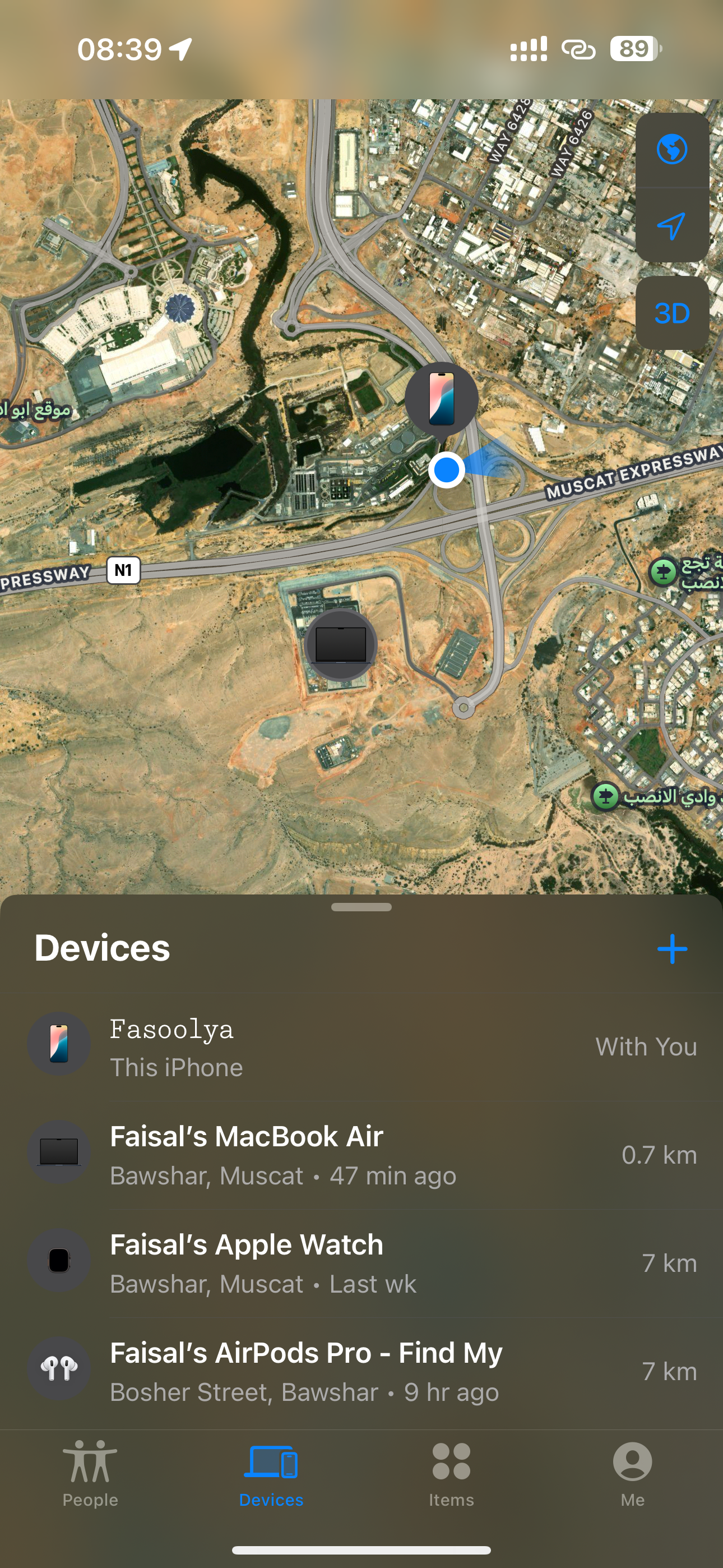

And with the real war quieting down, I started to feel in control over myself again. Over where I was, where I’d go, what’d happen next. I began tracking my luggage using Find My, since my MacBook was inside one of the bags.

And what was initially a feeling of dread— of being alone in a foreign country— turned into one of odd serenity. I was still alone, sure. But you and your people helped me take back the wheel, and I was so deeply grateful for that. At one point, I even found myself hoping the luggage would take longer to arrive, just so I could keep wandering Muscat and meet more people.

After 8 days of wandering Oman in awe, my screen lit up: my MacBook was in Muscat. A notification came through. My luggage had arrived.

It was a bittersweet moment, but I booked my flight back to Doha for later that afternoon.

8 days ago, I was on board a military transport plane. Now I was sitting on the window seat of a SalamAir commercial airplane. I reflected on what I had felt last time. That funny feeling. I had come full circle. Oh, the quiet way in which life— almost mechanically— becomes symmetric. How funny, to be airborne again. I recalled the Khayyam quatrain once more, but now the full quatrain, complete with the first couplet.

نیکی و بدی که در نهاد بشر است

شادی و غمی که در قضا و قدر است

با چرخ مکن حواله کاندر ره عقل

چرخ از تو هزار بار بیچارهتر است

The good and evil that dwell in human nature,

The joy and sorrow decreed by fate and destiny—

Blame not the heavens through the reasoning mind,

For the heavens are a thousand times more wretched than you.

I had previously resigned myself to the wretched decrees of heaven in that warplane. Blamed them for the mercilessness of the universe. But now, suspended over a calmer sky, I realized that the quatrain began inwards, not outwards. It doesn’t open with the stars or heaven or fate, but with the good and evil in human nature. Before destiny ever intervenes, we are already made of choice. Even if sorrow is written in the stars, goodness is not. Goodness is a choice. It lives in the same human nature that holds cruelty, and it cannot be imposed by the heavens or excused by them either.

Your people chose goodness. Against the cosmos’ decree of sorrow, they choose it. Again and again. And that taught me that even if fate may define the conditions, it is human nature that determines the response.

And now I realize that the quatrain never blamed the heavens— they are a thousand times more wretched than us. It pitied them. They are a thousand times more wretched than us. That line used to feel bitter to me. Resigned. But I think on this SalamAir commercial plane– of all places— I finally understood it. The line wasn’t about surrender, it was about letting go of blame, and finding meaning in the only thing we ever truly hold: the self.

I repeated the full couplet to myself, softly this time. I felt the peacefulness of sleep take over my body, slowly. Through relaxed teeth, I sang it again and again, letting its completeness— my newfound understanding of it— carry me. The engines on this plane hummed too, but they no longer drowned me out. I let the couplet join their hum, not as a chorus of mourning, but one of meaning.

And I drifted off to this duet, knowing that being carried was enough.

And so, dearest Oman, I am eternally grateful for what you did to me.

In June, I was forcefully made aware of the illusion of peace. you showed me what it truly looked like.

That peace was not silence or distance.

Not numbness or indifference either.

That peace was the quiet strength of people who choose goodness against the odds.

That peace was in the warmth of the tea offered to strangers.

You taught me that peace is not the absence of sorrow—

Sorrow was an inextricable part of peace,

peace is what we do with it

Yours truly,

Faisal Toosan